16 Jun 2025

Mystery Marketing in Action: Lessons from Psycho, The Matrix & Inception

Table Of Content

Table of Contents

Before social media timelines determined our awareness and trailer drops came with countdowns, there were movies that didn’t just sell tickets — they sold ideas. Ideas so radical that they cannot be encapsulated in a sentence. Stories that refused to be consumed; they needed to be deciphered. But how do you sell a film when its genius is reliant on the twist? When the spoiler is the essence of the story?

You don’t give it away. You let the audience pursue it.

Psycho, The Matrix, and Inception were not only successful because of their visionary filmmaking. They were effective because they used mystery marketing campaigns that demanded curiosity, participation, and restraint. These were not merely marketing campaigns — they were psychological marketing tactics.. And the battlefield was in the mind.

These three genre-defining films redefined the very idea of promoting a movie.

Psycho: Turning Suspense into a Mystery Marketing Weapon

By 1960, Alfred Hitchcock was a master of suspense, but with Psycho, he became a master of anticipation. What he made was not merely a marketing campaign but a ritual.

There was a rule: no latecomers allowed. Posters outside theaters warned filmgoers: “No one will be admitted after the start of the picture.” This was unheard of at the time. But it wasn’t really about punctuality — it was about control. Hitchcock hoped that audiences would see the movie precisely as he’d intended them to: with no spoilers, no hints, and no opportunity to reconstruct a moment that’d just transpired.

He refused advanced screenings. He made his cast and crew sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). He even purchased the rights to the novel to prevent the twist from being given away. The studio said he was insane. But the crowd had thought he was brilliant. Lines snaked around city blocks and the ticket sales surged. There was a viral spread of curiosity. In that silence—in that total lack of information, the suspense flourished.

Psycho was more than a horror movie. It was a masterclass in manipulating expectations, and Hitchcock didn’t have to rely on marketing budgets to do it. He weaponized secrecy. He created a kind of sacred space out of the unknown. And by doing so, he turned the simple act of watching a film into a cultural event. Psycho’s storytelling marketing was way ahead of its time.

For more insights into groundbreaking movie marketing strategies, check out

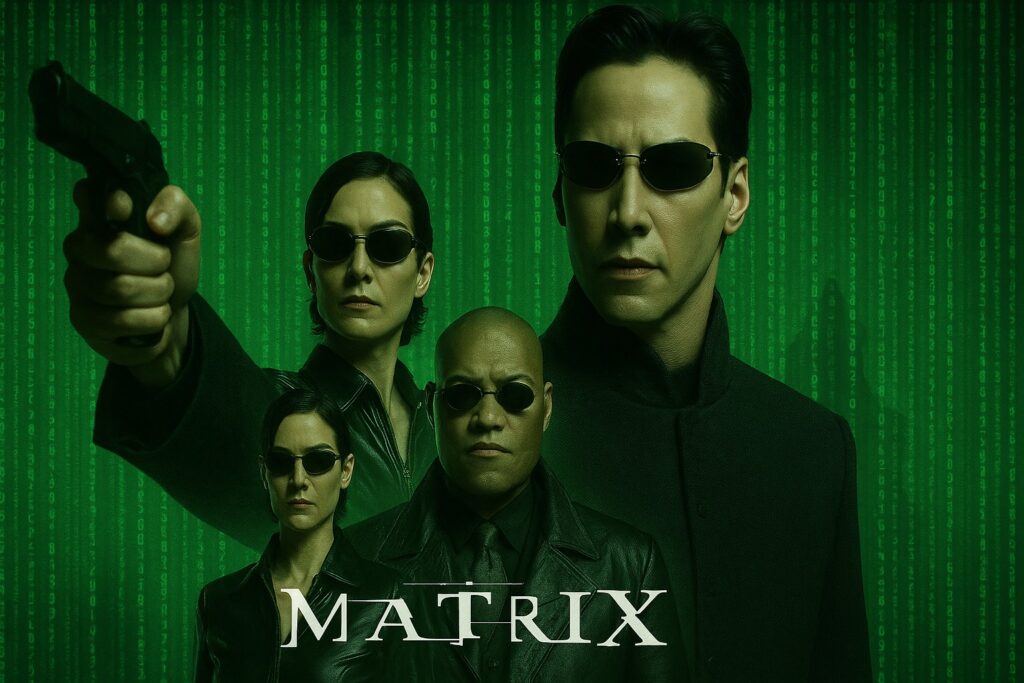

The Matrix: Viral Marketing Before Social Media

It was the year that was filled with fears of Y2K, tech booms, the internet coming of age. The Matrix was the first movie like no other to break out into that digital fog — a film that read like sci-fi but played like scripture. It doubted reality itself — and the campaign reflected that doubt.

“What is The Matrix?” That was the tagline. That was the question. And no one had the answer. The trailers teased enigmatic images: kung-fu in slow-motion, bullets dodged in midair, people unplugged from pods. But the plot? Completely unknown. It wasn’t a teaser; it was a dare.

The site didn’t describe the movie at all. It deepened the riddle. It was interactive, mysterious, a digital breadcrumb trail. Long before there was a name for viral marketing, The Matrix was living it. It was the first film to be able to incorporate online ambiguity into the experience. On the web, fans were gossiping, theorizing, and exchanging clues. The audience was fully integrated into the simulation.

It was not about revealing the content. It was a gesture that made people uneasy; a silent revolt against spoon-fed trailers. The campaign aligned closely with the theme of the film: what if what you know is not true?

By the time audiences made their way into the theater, they were not just viewers, but seekers. Ready to be unplugged.

Inception: A Masterclass in Storytelling Marketing

It’s no secret that Christopher Nolan doesn’t traffic in easy movies, and Inception was his most intricate labyrinth to date. It was a film about dreams within dreams within dreams. The gamble was huge: how do you sell something that nobody may even understand until the third viewing?

The solution: you don’t simplify it, you elevate it.

The trailers provided the audience with atmosphere, not answers. Buildings being destroyed, Zero-gravity hallways, a spinning top, and a loaded question: “What is the most resilient parasite? An idea.” That was the hook — not a hint at the plot, but a call to a philosophical question.

Nolan relied on the audience to lean in, not tune out. Layering was the spirit of the film, and the campaign. Posters didn’t show faces — they showed buildings. Sound design emerged as a focal point, that signature “BRAAAM” through theaters and memes alike. Visuals outweighed dialogue for a change. This campaign wasn’t about clarity; It was about curiosity.

Warner Bros. didn’t just sell the film — they planted it, like an idea, in the minds of audiences. And that’s essentially what Inception was about. Not the heist, not the dreams — the faith.

It proved that psychological marketing tactics and complex storytelling marketing are a major part of blockbuster cinema.

The Art of Mystery Marketing: How Movies Became Marketing Legends

In a time of aggressive marketing and over-explaining trailers, Psycho, The Matrix and Inception are fitting reminders of a lost art: leaving the audience to wonder. Both films made a virtue of restraint. They didn’t sell the what. They sold the why.

And these were not merely savvy promotions — they were mystery marketing campaigns turned into meta-experiences. Marketing that reflected the film’s very DNA. The Psycho was also about the power of surprise. The Matrix on the concept of free will. Inception seduced audiences with the idea of dreams within dreams. Their campaign wasn’t a distraction from the story; it was the preface.

And perhaps that’s the secret: great movie marketing doesn’t overexplain — it leaves space to wonder.

It leaves you uneasy. Curious. Electrified by the unknown.

FAQs: Mystery Marketing in Movies

1. What is mystery marketing, and how is it used in movies?

Mystery marketing is when a film doesn’t reveal its story or key twists but encourages audiences to discover them for themselves. Movies like Psycho, The Matrix, and Inception used mystery marketing campaigns that demanded curiosity, participation, and restraint, turning movie watching into a psychological and cultural experience.

2. How did Psycho use psychological marketing tactics to create suspense?

Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho weaponized secrecy to build anticipation. He refused advanced screenings, made his cast and crew sign NDAs, purchased the novel’s rights, and warned audiences: “No one will be admitted after the start of the picture.” This created a viral spread of curiosity and a sacred space of suspense.

3. How did The Matrix use viral marketing before social media?

The Matrix released enigmatic trailers and a tagline asking, “What is The Matrix?” Its website deepened the riddle without explaining the plot. Fans shared clues, theories, and gossip online, making the audience part of the experience.

4. How did Inception use storytelling marketing to promote its complex plot?

Inception used storytelling marketing by giving audiences an atmosphere instead of answers. Trailers and posters highlighted visuals, sound, and philosophical questions, inviting viewers to engage with the layered plot. This approach showcased how psychological marketing tactics and complex storytelling marketing can make a blockbuster memorable.

5. Why does mystery marketing work so well for movies?

Mystery marketing works because it doesn’t reveal everything upfront—it leaves space for curiosity and engagement. Films like Psycho, The Matrix, and Inception created suspense, intrigue, and interactive experiences that turned audiences into seekers, showing that mystery marketing campaigns, psychological marketing tactics, and storytelling marketing can make a film memorable and culturally significant.

Also Read:- Social Proof in Marketing: How It Hacks the Consumer Mind

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Comments